What is FLIR MSX? An Analysis of Contextual Thermal Imaging

Update on Nov. 6, 2025, 9:52 a.m.

The world we perceive with our eyes is only a narrow band of the electromagnetic spectrum. Just beyond the “visible light” we see lies the “infrared” spectrum—a vast, invisible landscape of heat energy. Everything with a temperature above absolute zero radiates this energy. A thermal camera is a device that translates this invisible heat map, or “thermogram,” into a picture we can see.

For decades, this technology was prohibitively expensive. The recent availability of low-cost thermal imagers, such as the #1 Best Seller FLIR ONE Gen 3 (ASIN B0728C7KND), has given this “superpower” to homeowners, technicians, and DIYers.

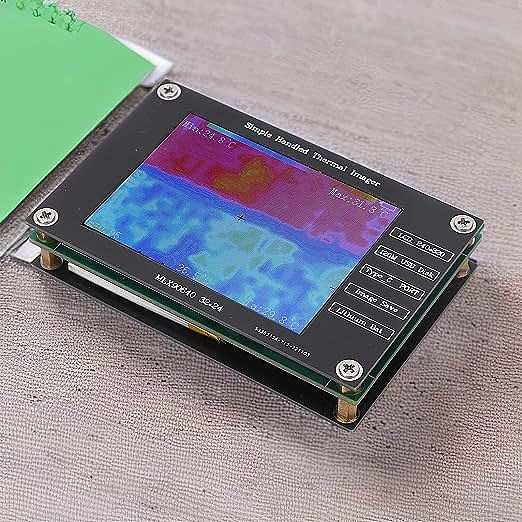

However, this accessibility comes with an engineering trade-off. Entry-level sensors have a very low thermal resolution. The FLIR ONE Gen 3, for example, has an 80x60 sensor, producing a raw thermal image of only 4,800 pixels. The result is often a colorful, blurry “blob” (as seen in the 3.7-star “Picture quality” rating), which presents a significant “context problem”: you can see a hot spot, but you can’t tell what it is.

This is where a patented image processing technology, MSX®, becomes the critical factor that transforms a low-resolution “toy” into a high-utility “tool.”

What is FLIR MSX® Technology?

MSX, or Multi-Spectral Dynamic Imaging, is an engineering solution to this “context problem.” It is a sophisticated, real-time image processing algorithm that requires a crucial piece of hardware: two cameras.

Devices equipped with MSX, like the FLIR ONE, feature both:

1. A Thermal Camera (a low-resolution sensor that captures the heat data, or “thermogram”).

2. A Visible Light Camera (a standard camera that captures the physical “outline” data).

As the user points the device, an onboard processor analyzes the feed from both cameras simultaneously. It doesn’t just “blend” the two images, which would result in a washed-out, semi-transparent picture.

Instead, the MSX processor identifies the high-contrast edges, outlines, and textures from the visible image (e.g., the outline of a circuit breaker, the text on a sign, the edges of a window frame) and “embosses” this structural detail directly onto the pure thermal image.

The result is a single, fused image. The user gets the thermal data from the heat sensor, but it is mapped directly onto the recognizable context of the visible world. The hot “blob” is instantly identifiable as a specific electrical outlet, a water stain, or a pet hiding in the dark.

MSX vs. High Resolution: The Context-vs-Data Trade-Off

This “contextual” approach is the key to the FLIR ONE’s market dominance, even when compared to competitors with superior thermal specs.

A user review in the product data, for example, compares the 80x60 resolution FLIR ONE Gen 3 to the 320x240 resolution SEEK Compact Pro. The SEEK Pro has a much higher resolution sensor (76,800 pixels vs. 4,800) and a wider temperature range. However, it lacks an MSX-style contextual overlay.

For many diagnostic tasks, especially at close range, the “context” provided by MSX is more valuable than the “raw data” of a higher-resolution sensor. A high-res thermal image may still be a “blurry blob” if the object and its surroundings are near the same temperature. MSX solves this by forcing the visible-light context onto the image. This is a deliberate trade-off: FLIR invested in a sophisticated image processing solution (software) rather than a more expensive sensor (hardware), hitting a price point that makes the tool accessible.

Practical Applications of MSX-Enabled Imaging

This fusion of heat and context unlocks immediate, actionable diagnoses that are difficult with a thermal-only sensor.

- Energy Audits: A cold spot on a wall is just a “blob.” With MSX, that cold spot is clearly embossed with the outline of the window frame or electrical outlet it’s seeping through, identifying the exact source of the draft.

- Water Damage: Evaporating water creates a cold signature. A raw thermal image shows a cold patch. An MSX image shows the cold patch and the visible-light outline of the ceiling joist it’s following or the faint water stain it’s associated with.

- Electrical Inspections: A hot circuit breaker is a serious fire hazard. A raw thermal image might show a warm area on a breaker panel. An MSX image shows the specific breaker switch, clearly defined and labeled (if text is visible), that is overheating, removing all guesswork.

- Night Vision: In total darkness, the visible camera sees nothing, but the thermal camera sees the heat of a person or animal. The MSX algorithm is smart enough to default to the raw thermal image in this case, allowing it to function for finding pets or wildlife.

A Core Principle of Thermography: Emissivity

One critical principle of physics that MSX helps manage is emissivity. Emissivity is a measure of how well an object radiates its own heat.

- High Emissivity: Most organic materials, (skin, wood, drywall, paint) are excellent emitters. Their surface temperature is accurately read by the thermal camera.

- Low Emissivity: Shiny, reflective objects (like polished metal or a mirror) are terrible emitters. They are, however, excellent reflectors of thermal energy.

When a thermal camera is pointed at a shiny metal pipe, it is not accurately reading the pipe’s temperature. It is likely reflecting the “cold” temperature of the sky or the “hot” temperature of the technician’s own body. A raw thermal image would show a confusing “cold” spot. An MSX-enhanced image, however, also shows the visible-light shine and outline of the metal pipe, which immediately signals to a trained technician that the thermal data is unreliable due to low emissivity.

Conclusion

MSX is not just a marketing “feature”; it is a sophisticated image processing technology that fundamentally solves the “context problem” inherent in low-resolution thermal sensors. By intelligently embossing visible-light outlines onto the thermal heat map, it translates an ambiguous “blob” into an actionable, diagnostic image. This software-first approach is what made devices like the FLIR ONE Gen 3 accessible, popular, and—most importantly—useful.